Scientific research is finally starting to uncover the mysterious role of sleep in creativity, and no creative field seems to depend as intimately on the inmost workings of sleep as musical composition. In Western classical music history, the dreams of composers are cast in an almost mythic aura; composers from Schumann to Stravinsky have recounted fantastical experiences of their “best” compositions occurring to them in dreams. An abundance of contemporary composers and songwriters also see sleep, dreams, and the unconscious as wellsprings of creativity. The tune to the Beatles hit “Yesterday” occurred unexpectedly to Paul McCartney in a dream,[1] and musicians Billy Joel and Joseph Shabalala have claimed that they “‘hear’ all their compositions—minus words—in dreams.”[2] We have ample evidence that non-original music and original music occur in dreams and can later be recalled. In a study by Uga et al., 28% of participants’ dreams with musical content allegedly featured novel music—a fairly high rate compared to the 55% occurrence of familiar/known music.

The most recent scientific research on dreams and creativity often challenges one-dimensional hypotheses of dreaming like Freud’s wish fulfillment theory and Antii Revensuo’s threat simulation theory. For example, psychological researcher G. William Dornhoff argues that stimulus-independent thought in dreaming occurs in comparable neural conditions to those that also promote creativity and improvisation in waking. Evolutionary psychologist Barrett echoes Dornhoff’s argument that not every aspect of dreaming needs to have an explicit evolutionary purpose, classifying dreaming as “our brain thinking in a very different neurophysiologic state but still about all the same topics.”[3]

In all the literature I have found, from neuroimaging to psychoanalysis, there is a consensus that music creation, like dreaming, relies heavily on unconscious processes. When psychoanalysis emerged at the turn of the 20th century, promising to expose the deepest recesses of the human psyche, composers grew interested. For example, the Romantic composer Gustav Mahler briefly consulted with Sigmund Freud; the pioneering psychoanalyst traced Mahler’s hallmark musical style—uniting “high tragedy and light amusement”—to traumatic childhood encounters where happy music played during painful moments.[4] According to exciting contemporary academic research and neuroimaging, dreaming and musical creativity alike may rely on a shared network of several brain regions.[5] These findings corroborate composers’ anecdotal claims that dreams play a significant role in their creativity.

I. Western classical composers’ dreams

The most iconic account of novel classical music occurring in a dream is the story of Giuseppe Tartini’s Faustian deal with the Devil. In a dream, Tartini offered the Devil his soul in exchange for fulfilling his every wish.[6] When Tartini handed the Devil his violin, he played a sonata “of such exquisite beauty as surpassed the boldest flight of [his] imagination.”[7] When he awoke, the composer immediately tried to reproduce what he heard on his violin but bemoaned that the sonata he composed, although “the best” he ever wrote, failed to match the intensity of the Devil’s performance.[8]

The publication in 1740 of Devil’s Trill, which became Tartini’s best-known work,[9] seems to be the first of many instances of fantastical stories of dreams occurring to composers in biographical literature on Western classical composers. Could it be that composers, noting the fame that came to Tartini, realized that regaling fans with mysterious accounts of music received in dreams was… good marketing? Perhaps, in some cases. The more plausible explanation for the increase in composers’ dream narratives was that psychoanalysis, starting at the turn of the 20th century, invigorated a retrospective fascination with composers’ dreams.

Take, for example, a 1975 paper on Ludwig van Beethoven’s dreams by the historian Maynard Solomon, who could not be clearer about his intention to apply Freudian analysis to “delusional fantasies which provide an entrance into [Beethoven’s] unconscious life.”[10] In a letter to a friend named Tobias Haslinger on 10 September 1821, Beethoven writes that sleep deprivation caused him to spontaneously slumber (perhaps, nap) in his carriage.[11] He dreamed of taking a long journey to Jerusalem, then Tobias occurred to him, and at last the idea for a canon[12] with a tune based on the phrase “O Tobias Haslinger!” played in his dream.

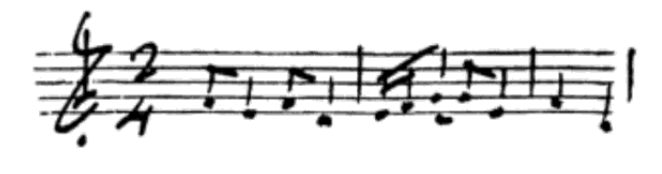

Although Beethoven could not recall the dream upon waking, he rode the same carriage the next day and, by way of association, continued playing the same “dream journey” in his waking mind.[13] This allowed him to hear the canon again and write it down. By Beethoven’s admission, he did not make the compositional choice of using three voices until this waking stage; in other words, he did not claim that the divine simply “downloaded” a completed work into his brain.[14] Another aspect differentiating Beethoven’s canon from Tartini’s sonata was that it was not an impressive piece, at least by Beethoven’s standards. Listening to the canon, it has the same juvenile humor as Beethoven’s “zany” correspondence with Tobias,[15] featuring male singers who incessantly repeat disjunct variations on the phrase “O Tobias.”[16]

The composer Robert Schumann dreamed, on 17 February 1854, that angels came and dictated music to him. When he woke up, he “copied the piece down from memory” as a 32-bar tune, which he later used as the theme for a set of variations.[17] What stands out about this anecdote is its brevity and lack of obstacle, which implies a certain effortlessness. Unlike Tartini, who considered the music he wrote down a pale imitation of his dreamed music, and unlike Beethoven, who struggled at first to remember his dreamed music, Schumann believed that he could recall new music from his dreams with accuracy and ease.

Psychoanalyst Alan Walker argues that such testimonies support the “existence of unconscious processes in our art,” or in other words, “a power that works within us without consulting us.”[18] As with dreams, the process of composing itself relies on mechanisms that do not operate consciously. Schumann himself recognized that it was “extraordinary” that he could write complex music first and then go back to analyze its sophisticated inner workings in retrospect.[19] Freud would shortly thereafter make a very similar claim about dreams: that their manifest content (“what happened?”) belies latent content (“what’s the deeper meaning?”) that can be revealed through psychoanalysis.[20] Walker compares composing to sleep: “Composers frequently sleepwalk their way through music, and, having safely reached the other side, turn round to observe with astonishment the many obstacles they negotiated to get there.”[21]

Surely the very process of musical creation is strongly associated with transcendence. The fact that Tartini and Schumann dreamed of devils and angels bequeathing musical treasures to them reflects their Christian understanding of the source of creativity.

The occurrence of visceral, emotionally charged images of devils, angels, and other striking imagery in these dreams may also owe much to the amygdala. Lai et al. hypothesize that “the amygdala functions as an emotional integration center for emotions in dreams,” based on evidence in the literature that the amygdala not only processes anxiety and fear in dreams but may also causally affect “dream duration, bizarreness, and vividness.” Stimulating their subjects’ amygdalas while they were awake caused the subjects to report “vivid, emotional, bizarre, and dynamic mental imagery closely resembling physiologic dreaming.”[22] For one subject, stimulation induced novel images of unfamiliar people, animals, demons, and various objects. The authors conclude with the hypothesis that “the human brain may rely on the same neural network to generate both dream and creativity related mental imagery, thoughts, and concepts.”[23]

Igor Stravinsky said in an interview that his music sometimes “appeared” to him in dreams.[24] The Russian composer’s musical dreams often featured striking visual elements. In one dream, he saw a young nomad sitting by the edge of the road, playing the violin for her son, who sat on her lap.[25] He noticed that the woman kept using the entire length of the violin bow to repeat a short musical phrase and that the child applauded the music.[26] Funny enough, Stravinsky was composing, at the time, L’Histoire du Soldat (Soldier’s Tale), based on a story in which a man gives over his soul and his violin to the devil. In this theatrical composition, the possessed soldier plays the tune that Stravinsky composed in his dream—a coincidental or perhaps non-coincidental echo of Tartini’s Faustian bargain three centuries prior.

II. Composers’ dreams in the past one hundred years

I had the good fortune of being a part of the massive audience at Yale’s Woolsey Hall for a conversation with Paul McCartney on February 16, 2023. With his winsome smile, the great songwriter regaled us with the origin story of the song “Yesterday.” He woke up one day in 1964 with the tune in his head and decided to play it on the piano. But doubting that the tune was his own, since it was “so good,” he played it for people for weeks to ask if they recognized it. Finally, he was convinced he received the tune in his dreams.

McCartney subtly authenticated his dream claim by emphasizing his amazement and his desire to confirm he was the tune’s original creator. But the American songwriter Billy Joel, like Beethoven and Schumann, expressed more certainty about his musical dreams and believed that he could recall them days or even weeks later:[28]

I’ve dreamt symphonies. And I know when I wake up that I just dreamt this complete piece of music—but I can’t remember what it is.[29]

As Joel describes it, he can often recover his dream music by sitting in his chair and waiting for a fully-realized piece to recur to him. In hindsight, he will recognize this music from an earlier dream. Billy Joel has also experienced more explicit “dream delivery” of music, such as the time he woke up next to his wife singing a gospel-inflected tune: “In the middle of the night, I go walking in my sleep.”[30] This fully-formed melody, with surprising lyrical coherence that exceeds Beethoven’s “O Tobias” canon, became the basis for the titular song on his album “River of Dreams.”[31]

Contemporary neuroscience offers compelling hypotheses that could explain why Billy Joel and so many other composers experience such uniquely fluid creativity during dreaming. Dornhoff offers the possibility that the brain state that occurs after “spontaneous morning awakenings” after dreaming or REM sleep may provide fertile ground for new ideas.[32] In this “nonthreatening context,” the default network, associated with drifting thoughts as well as the phenomena of music generation and appreciation, is lit up, whereas the sensory and executive functions of the brain are attenuated.[33] These neural conditions, where the “frontoparietal control network is attenuated and the default network is more active,” also occur in neuroimaging studies of creative activities.[34] Dreaming, in Dornhoff’s view, is the most extreme form of “stimulus-independent thought”: streams of thought unrelated to sensory input and freed from “conscious monitoring”.[35] As Billy Joel put it:

There’s no editor when you’re sleeping. There’s no limitations, no governor… And that’s good. When I’m conscious and I’m writing, I’m trying to be very efficient, very skillful… All that stuff should go out the window. I’m tapping into pure emotion when I’m dreaming.[36]

Dornhoff’s model would suggest that Billy Joel intuitively feels that his brain’s control network dominates during the day but less so at night. An oddity of Joel’s anecdotal experience, as well as Beethoven’s, is how these composers can retrieve their dreams after seemingly forgetting them upon their first awakening. According to psychiatry professor Ernest Hartmann offers a start at an explanation, the brain does not easily hold onto “less consciously directed thinking” like dreaming and mind-wandering. Hartmann asks, “Can you recall where your mind wandered while you were brushing your teeth this morning?” However, dreams can catch the attention of our brain when they have enough “emotional significance” (they perhaps involve a problem, a person, or a bizarre event), increasing activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).[37] By Hartmann’s hypothesis, when a composer’s dream has enough emotional charge, the DLPFC takes notice and encodes the dream into memory.

Joseph Shabalala, a celebrated South African composer,[38] experienced dreams so emotionally significant that they ultimately motivated him to lead Africa’s most popular vocal group ever, Ladysmith Black Mambazo.[39] For six months in 1964, a 24-year-old Shabalala dreamed that he was watching a choir of spirits[40] singing to him in an unknown language.[41] Shabalala felt ownership over the harmony and rhythm that emanated from these spirits, as if it was his original music. He began to sing out loud with the spirits every night in his dreams.[42]

In a later dream, Shabalala encountered a circle of elders who gave him a “final examination” to see if he was ready to become the composer-director of a traditional Zulu ensemble called an isachamiya.[43] This experience was consistent with the traditional Zulu belief in dreams as a medium connecting the living with their wise deceased elders.[44] While Freud conceived of dreams as “highly coded and personalized symbols,” the Zulu people held an alternative conception that more resembles Carl Jung’s notion that dreams connect individuals to the wealth of “ancestral experiences, symbols, and archetypes” in the “collective unconscious.”[45] Shabalala came to rely on his musical dream, calling it his “vision,” and finds that his effortless, relaxed state at night will often allow him to wake up the next morning having solved a nagging musical problem.[46]

Indeed, Western psychological research shows that problem-solving can be a common feature of dreaming—especially when subjects intentionally prime themselves to dream about their chosen problem,[47] much like the Zulu people traditionally do. A study by Deirdre Barrett showed that among college students who aimed to solve a problem by following “dream incubation” procedures formulated by William Dement for a week, half recalled a dream related to the problem, and of those, seventy percent dreamed of a solution.[48] Barrett qualifies this result by observing that problems of a “personal nature” were more likely to be seen as solved than those of an “academic or general objective nature.” She also cautions that the population of the study was a group with an unusual interest in dreams, and therefore not representative of the general population. Her results should instead be taken as systematic evidence that dreams about solving problems of a personal nature can be induced at decently high rates.

Perhaps music, as a highly emotional, tactile, and communitarian practice, is more readily embodied in dreams than its more cerebral counterparts like calculus or writing. An ethnographic study of jazz musicians by Paul Berliner notes several examples of tactile musical embodiment in dreams.[49] John Coltrane dreamed he received counsel and encouragement from his idol, Charlie Parker, to continue innovating with intricate chord substitutions. Jerry Coker saw his hands methodically working through a difficult piano solo in his dreams and awoke to find, to his delight, that his finger patterns had improved. As Ballantine writes, we need much more research on the neural mechanisms that drive subconscious musical problem-solving in the many cultural contexts where it occurs.

I informally asked a few undergraduate composers at Yale to share their experiences of musical dreams. Sharon Ahn ‘24 said that they “often wake up frustrated” about not being able to remember the music in their dreams, which is often vividly orchestrated. One time, they successfully sang a simpler bassline melody into their phone upon waking. Multiple composers cited intense or bizarre visual imagery, lending support to Lai et al.’s hypothesis on the amygdala’s visual mediation of creative dreams.

In the only composing dream that Noah Stein ‘25 recalls, he floated across giant metallic staves. He “saw new notes appear” and heard each note sound out loud as it passed.

Omeno Abutu ‘27 once woke up with a start because a new melody, paired with a “very vivid visual,” had been “disturbing” her as she slept. She recorded herself singing the melody right away. Omeno also observed that whenever she works hard on a piece during the day, she will have it in her head as she sleeps that night; she wakes up feeling like she has thought very intensely about it, without remembering what her thoughts were. As for myself, I often forget the music in my dream within the moment of waking, but one or two times a year, I can open Voice Memos or grab a piece of paper in time to capture the idea.

I also share in Omeno’s experience that when I want to approach my music refreshed and inspired, there’s nothing like a good night of sleep.

[1] “Dreams and Creative Problem-Solving”

[2] Dornhoff

[3] “Dreams and Creative Problem-Solving”

[4] Walker 1642

[5] Lai et al.; Dornhoff

[6] Walker 1641

[7] Tartini, qtd. in Walker 1641

[8] Walker 1641

[9] Schwarm

[10] Solomon 113

[11] Solomon 122

[12] A canon, also known as a round, is a common musical device where the same tune is produced by multiple voices, but the voices begin at different times, creating a multilayered and often complex contrapuntal structure.

[13] Solomon 122

[14] Solomon 122

[15] Solomon 124

[16] Solomon 123

[17] Walker 1641

[18] Walker 1642

[19] Walker 1642

[20] Borges 9

[21] Walker 1642

[22] Lai et al.

[23] Lai et al.

[24] Craft 17

[25] Craft 17

[26] Craft 18

[27] Craft 17

[28] Considine

[29] McCartney qtd. in Considine

[30] Considine

[31] Considine

[32] Dornhoff

[33] Dornhoff; Lopéz-González and Limb

[34] Dornhoff

[35] Liu et al., qtd. in Dornhoff

[36] Considine

[37] Hartmann

[38] Ballantine 5

[39] Denselow

[40] Shabalala calls them “children of God,” meaning that he perceived these choristers as humans but only in a vague form lacking apparent age, gender, or race (5).

[41] Ballantine 5

[42] Ballantine 5

[43] Ballantine 6

[44] Ballantine 7

[45] Ballantine 7; Borges 14

[46] Ballantine 10

[47] “The ‘Committee of Sleep’”

[48] “The ‘Committee of Sleep’”

[49] Ballantine 9

Bibliography

Barrett, Deirdre. “Dreams and Creative Problem-Solving.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1406, no. 1 (October 1, 2017): 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13412.

Boilly, Louis-Léopold. “Tartini’s Dream.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1824, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/57884.

Borges, Helen. “Sleep, Dreams and Psychology.” The Mystery of Sleep, 26 October 2023, Yale University, New Haven, CT. PowerPoint presentation.

Considine, J.D. “Billy Joel: Afloat on a River of Dreams.” Baltimore Sun, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1993-10-17-1993290239-story.html.

Craft, Robert. Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. Faber & Faber, 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=3ZZKAQAAQBAJ.

Denselow, Robin. “Joseph Shabalala Obituary.” The Guardian, February 14, 2020, sec. Music. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/feb/14/joseph-shabalala-obituary.

Domhoff, G. William. “Does Dreaming Have Any Adaptive Function(s)?” In The Emergence of Dreaming: Mind-Wandering, Embodied Simulation, and the Default Network, edited by G. William Domhoff. Oxford University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190673420.003.0009.

Barrett, Deirdre. “The ‘Committee of Sleep’: A Study of Dream Incubation for Problem Solving.” Dreaming, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1993. https://www.asdreams.org/journal/articles/barrett3-2.htm.

Hartmann, Ernest. “Why Do Memories of Vivid Dreams Disappear Soon After Waking Up?” Scientific American, May 1, 2011. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-do-memories-of-vivid-dreams/.

Lai, George, Jean-Philippe Langevin, Ralph J. Koek, Scott E. Krahl, Ausaf A. Bari, and James W. Y. Chen. “Acute Effects and the Dreamy State Evoked by Deep Brain Electrical Stimulation of the Amygdala: Associations of the Amygdala in Human Dreaming, Consciousness, Emotions, and Creativity.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 14 (2020). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00061.

López-González, Mónica, and Charles J. Limb. “Musical Creativity and the Brain.” Cerebrum: The Dana Forum on Brain Science 2012 (February 22, 2012): 2.

Schwarm, Betsy. “The Devil’s Trill.” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Devils-Trill.

Solomon, Maynard. “The Dreams of Beethoven.” American Imago 32, no. 2 (1975): 113–44.

Uga, Valeria, Maria Chiara Lemut, Chiara Zampi, Iole Zilli, and Piero Salzarulo. “Music in Dreams.” Consciousness and Cognition 15, no. 2 (June 1, 2006): 351–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.003.

Walker, Alan. “Music And The Unconscious.” The British Medical Journal 2, no. 6205 (1979): 1641–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25438227.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.